As service oriented architecture (SOA) begins to become widely adopted through organizations, there will be major dislocations in the balance of power and control within IS organizations.

As service oriented architecture (SOA) begins to become widely adopted through organizations, there will be major dislocations in the balance of power and control within IS organizations. In this paper when we refer to information systems (IS) line functions, we mean those functions that are primarily aligned with the line of business systems, especially development and maintenance. When we refer to the IS staff functions, we’re referring to functions that maintain control over the shared aspects of the IS structure, such as database administration, technology implementation, networks, etc.

What is Service Oriented Architecture?

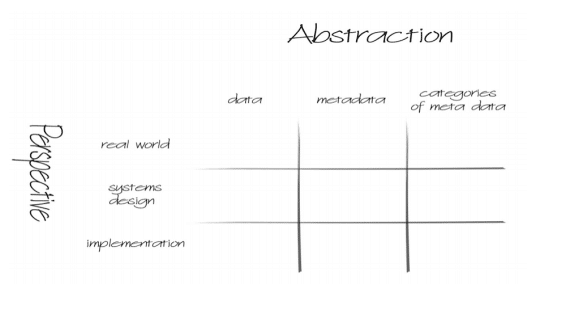

Service oriented architecture is primarily a different way to arrange the major components in an information system. There are many technologies involved with SOA that are necessary in order to implement an SOA and we will touch on them briefly here; but the important distinction for most enterprises will be that the exemplar implementations of SOA will involve major changes in boundaries between systems and in how systems communicate.

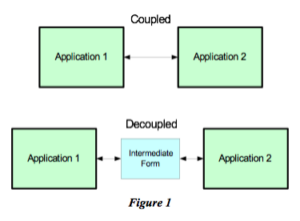

In the past, when companies wished to integrate their applications, they either attempted to put multiple applications on a single database or wrote individual interfacing programs to connect one application to another. The SOA approach says that all communication between applications will be done through a shared message bus and it will be done in messages that are not application-specific. This definition is a bit extreme for some people, especially those who are just beginning their foray into SOA, but this is the end result for the companies who wish to enjoy the benefit that this new approach promises.

A message is an XML document or transaction that has been defined at the enterprise level and represents a unit of business functionality that can be exchanged between systems. For instance, a purchase order could be expressed as an HTML document and sent between the system that originated it, such as a purchasing system, and a system that was interested in it, perhaps an inventory system.

The message bus is implemented in a set of technologies that ensure that the producers and consumers of these messages are not talking directly to each other. The message bus mediates the communication in much the same way as the bus within a personal computer mediates communication between the various subcomponents.

The net result of these changes is that functionality can be implemented once, put on the message bus, and subsequently used by other applications. For instance, logic that was once replicated in every application (such as production of outbound correspondence, collection on receivables, workflow routing, management of security and entitlements), as well as functionality that has not existed because of a lack of a place to put it (such as enterprise wide cross-referencing of customers and vendors), can now be implemented only once. [Note to self: I think that sentence is not correct anymore.] However, in order to achieve the benefits from this type of arrangement, we are going to have to make some very fundamental changes to the way responsibilities are coordinated in the building and maintaining of systems.

Web Services and SOA

Many people have confused SOA with Web services. This is understandable as both deal with communications between applications and services over a network using XML messages. The difference is that Web services is a technology choice; it is a protocol for the API (application programming interface). A service oriented architecture is not a technology but an overall way of dividing up the responsibilities between applications and having them communicate. So, while it is possible to implement an SOA using Web services technology, this is not the only option. Many people have used message oriented middleware, enterprise application integration technologies, and message brokers to achieve the same end. More importantly, merely implementing Web services in a default mode will not result in a service oriented architecture. It will result in a number of point-to-point connections between applications merely using the newest technology.

Now let’s look at the organizational dynamics that are involved in building and maintaining applications within an enterprise.

The Current Balance of Power

In most IS organizations, what has evolved over the last decade or so is a balance of power between the line organizations and the staff organizations that looks something like the following.

In the beginning, the line organizations had all the budget, all the power, and all the control. They pretty much still do. The reason they have the budget and the power is that it’s the line organization that has been employed to solve specific business problems. Each business problem brings with it a return on investment analysis which specifies what functionality is needed to solve a particular business problem. Typically, each business owner or sponsor has not been very interested or motivated in spending any more money than needed to in order to solve anyone else’s problem.

However, somewhere along the line some of the central IS staff noticed that solving similar problems over and over again, arbitrarily differently, was dis-economic to the enterprise as a whole. Through a long series of cajoling and negotiating, they have managed to wrest some control of some of the infrastructure components of the applications from the line personnel. Typically, the conversations went something like, “I can’t believe this project went out and bought their own database management system, paid a whole bunch of money when we already have one which would’ve worked just fine!” And through the process, the staff groups eventually wrested at least some degree of control over such things as choice of operating systems, database management systems, middleware and, in some cases, programming languages. They also very often had a great deal of influence or at least coordination on data models, data naming standards, and the like. So what has evolved is a sort of happy peace where the central groups can dictate the technical environment and some of the data considerations, while the application groups are free to do pretty much as they will with the scope of their application, functionality, and interfaces to other applications.

For much of the same reason, the decentralization of these decisions leads to dis-economic behavior, however, it is not quite as obvious because the corporation is not shelling out for another license for another database management system that isn’t necessary.

The New World Order

In the New World, the very things that the line function had most control of, namely the scope, functionality, and interfaces of its applications, will move into the province of the staff organization. In order to get the economic benefit of the service oriented architecture, the main thing that has to be determined centrally for the enterprise as a whole is: what is the scope of each application and service, and what interfaces is it required to provide to others?

In most organizations, this will not go down easily. There’s a great deal of inertia and control built up over many years with the current arrangement. Senior IS management is going to have to realize that this change needs to take place and may well have to intervene at some fairly low levels. As Clayton Christensen stated in his recent book The Innovator’s Solution, the strategic direction that an enterprise or department takes doesn’t matter nearly as much. What matters is whether they can get agreement from the day-to-day decision makers who are allocating resources and setting short-term goals. For most organizations, this will require a two-pronged attack. On one hand, the senior IS management and especially the staff function management will have to partner more closely with the business units that are sponsoring the individual projects. Part of this partnering and working together will be in order to educate the sponsors on the economic benefits that will accrue to the applications that adhere to the architectural guidelines. While at first this sounds like a difficult thing to convince them of, the economic benefits in most cases are quite compelling. Not only are there benefits to be had on the individual or initial project but the real benefit for the business owner is that it can be demonstrated that this approach leads to much greater flexibility, which is ultimately what the business owner wants. This is really a governance issue, but we need to be careful and not confuse the essence of governance, with the bureaucracy that it often entails.

The second prong of the two-pronged approach is to put a great deal of thought into how project managers and team leads are rewarded for “doing the right thing.” In most organizations, regardless of what is said, most rewards go to the project managers who deliver the promised functionality on time and on budget. It is up to IS management to add to these worthwhile goals equivalent goals aimed at contributing to and complying with the newer, flexible architecture, such that a project that goes off and does its own thing will be seen as a renegade and that regardless of hitting its short-term budgets, the project managers will not be given accolades but instead will be asked to try harder next time. Each culture, of course, has to find its own way in terms of its reward structure but this is the essential issue to be dealt with.

Finally, and by a funny coincidence, the issues that were paramount to the central group, such as choice of operating system, database, programming language, and the like, are now very secondary considerations. It’s quite conceivable that a given project or service will find that acquiring an appliance running on a completely different operating system and database management system can be far more cost-effective, even when you consider the overhead costs of managing the additional technologies. This difference comes from two sources. First, in many cases, the provider of the service will also provide all the administrative support for the service and its infrastructure, effectively negating any additional cost involved in managing the extra infrastructure. Second, the service oriented architecture implementation technologies shield the rest of the enterprise from being aware of what technology, language, operating system, and DBMS are being used, so the decision does not have the secondary side effects that it does in pre-SOA architectures.

Conclusion

To wrap up, the move to service oriented architecture is not going to be a simple transition or one that can be accomplished by merely acquiring products and implementing a new architecture. It is going to be accompanied by an inversion in the traditional control relationship between line and staff IS functions.

In the past the business units and application teams they funded determined the scope and functionality of the projects, the central IS groups determined technology and to some extent common data standards. In the service oriented future these responsibilities will be move in the opposite direction. The scope and functionality of projects will be an enterprise wide decision, whilst individual application teams will have more flexibility in the technologies they can economically use, and the data designs they can employ.

The primary benefits of the architecture will only accrue to those who commit to a course of action where the boundaries, functionality, and interface points of their system will no longer be delegated to the individual projects implementing them but will be determined at a corporate level ahead of time and will merely delegate the implementation to the line organization. This migration will be resisted by many of the incumbents and the IS management that wishes to enjoy the benefits will need to prepare themselves for the investment in cultural and organizational change that will be necessary to bring it about.

that term? It is an instructive question because very often CRM (Customer Relationship Management) systems or other sales analytic systems group customers and sales based on their “market”. However, if we don’t have a clear understanding of what a market is, we misrepresent and misgroup and therefore mislead ourselves as we study the implication of our advertising and promotional efforts.

that term? It is an instructive question because very often CRM (Customer Relationship Management) systems or other sales analytic systems group customers and sales based on their “market”. However, if we don’t have a clear understanding of what a market is, we misrepresent and misgroup and therefore mislead ourselves as we study the implication of our advertising and promotional efforts.

guid style with their large unwieldy and mostly unnecessarily long strings.

guid style with their large unwieldy and mostly unnecessarily long strings.

conference (OOPSLA in 1986): highly biased toward academic and research topics, at the same time shining a light on the issues that are likely to face the industry over the next decade. In this write up I’ll try to capture the tone of the conference, what seemed to be important and what some of the more interesting presentations were.

conference (OOPSLA in 1986): highly biased toward academic and research topics, at the same time shining a light on the issues that are likely to face the industry over the next decade. In this write up I’ll try to capture the tone of the conference, what seemed to be important and what some of the more interesting presentations were.